The 2nd

LaureateSculpture

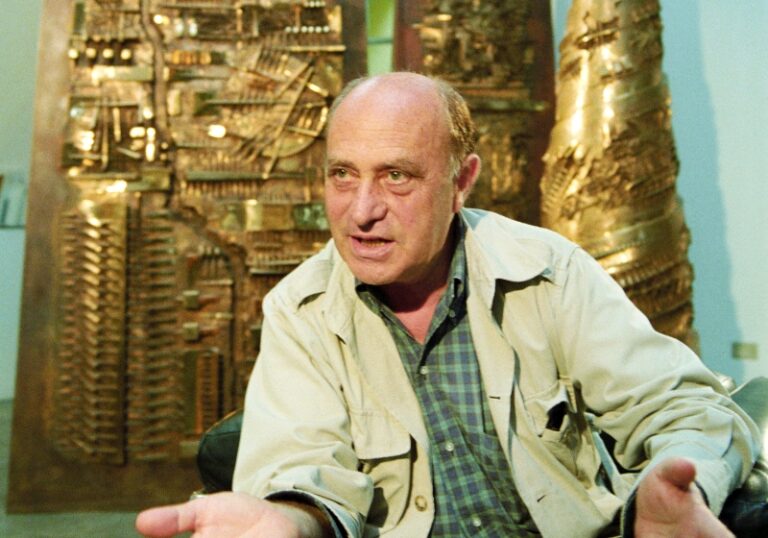

Arnaldo Pomodoro

Pomodoro initially trained as an architect and in the theatre,and this experience is evident in his sculptural work: always dramatic and sumptuous,it is also extremely responsive to the surrounding environment. He was profoundly influenced by an encounter with a Brancusi sculpture,envisaging ‘the coherent form broken into pieces’. He began making smooth-surfaced forms which were dramatically ripped open to reveal the workings of some apparently technological mechanism within. Using this technique as an analogy for the dualities of life – appearance and reality,body and mind,language and thought – Pomodoro has worked on an ever more public scale,with sculptures in major public spaces in New York,Rome and Moscow. Yet for all his modernity,Pomodoro can also be compared to Piero della Francesca,another Italian who combined the technological with the archaic.

Biography

Like many leading modern sculptors,Arnaldo Pomodoro originally trained as an architect; he also studied stage design and served an apprenticeship as a goldsmith,later working on jewellery in partnership with his younger brother Giò,who also became a sculptor. All of these experiences fed into Pomodoro’s later practice. His sculptural work is dramatic and sumptuous,but also extremely responsive to the surrounding environment.

Brought up in Umbria,Pomodoro settled in Milan in 1954,where he had his first solo exhibition the following year. Like many of the young Italian artists of that period he was attracted to the new abstraction derived from American abstract expressionism: in Europe this new abstraction became known as informalism. For Pomodoro this description was somewhat misleading,since his work was always guided by the profound feeling for formal relationships which he had gained from his architectural training. His earliest works were reliefs which seem like maps of imaginary cities. One influence on them,in addition to informalism,was the playful,semi-abstract work of Paul Klee; another,more traditional influence was the Florentine renaissance sculptor Ghiberti,particularly his reliefs on the monumental bronze doors of the Baptistery in Florence.

In 1960 Pomodoro went to New York,where he met the American sculptors David Smith and Louise Nevelson. He had a kind of epiphany when standing in front of a bronze by Brancusi in the Museum of Modern Art; he envisaged,he says,‘the coherent form broken in pieces’. Nineteen-sixty also marked the beginning of Pomodoro’s fascination with technology. He began to create smooth and almost minimal forms which were dramatically ripped open to reveal the forms of an apparently intricate technology hidden within. This process of ripping and tearing was in part influenced by the work of the Italian painter and sculptor Lucio Fontana,who was at that time attracting considerable attention with his slashed canvases. With his work of the 1960s Pomodoro’s reputation rose rapidly; in 1963 he was awarded the first prize for sculpture at the São Paulo Bienal and in the following year the National Prize for Sculpture at the Venice Biennale. Throughout the decade his work continued to develop. In 1966 he began to use what was to become one of his most characteristic forms – the sphere – and towards the end of the decade shifted momentarily towards a kind of minimalism.

Pomodoro has always,however,remained keenly conscious of the Mediterranean past. Athough his sculpture is always recognisably modern,it is also like that of a very different sculptor,Henry Moore,in the degree to which it alludes to ancient civilisations. As well as spherical forms,he has made much use of discs,columns and pyramids,all of which can be read as references to the past – the pyramids to Ancient Egypt; the columns to classical Greece and Rome,and the discs to Aztec calendar stones. It was the form of Aztec calendar stones which partly inspired one of his best-known monumental works,Disco Solare,placed in front of the Youth Building in Moscow in 1991. This was the first major sculpture by a western modernist to appear in Russia after the fall of communism. Pomodoro is keenly aware of the effect which these simple but culturally resonant forms have as objects placed within a particular space. He is also aware of the way in which his polished metal surfaces dissolve the form of his sculptures and also pull in forms and colours from the surrounding environment. In this sense,his original training as a theatrical designer has remained very much part of his work,and it is not surprising that he has continued to work in the theatre throughout his career. Some of his most memorable contributions to the theatre were made in the 1980s,notably his designs for the Rossini opera Semiramide at the Rome Opera in 1982,and for the Agamemnon of Aeschylus in 1983. These designs offer a clue to the literary influences in his work,which include not only the plays of Aeschylus,but also those of Sartre and Brecht.

Pomodoro stands apart from almost all of his contemporaries in being an artist who recognisably forms part of the visionary tradition. Some of the most relevant comparisons prompted by his sculptures are not with works by any of his contemporaries but with that of late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century architects such as Etienne-Louis Boullée and Karl Friedrich von Schinkel. Another artist who is relevant to the nature of Pomodoro’s achievement is Piero della Francesca – in his own time both technological and archaic. The comparison is appropriate for more than one reason: Pomodoro himself says that,when he was young,Piero was the very first artist of whom he became aware. In a certain sense Piero can be said to have presided over the whole of Pomodoro’s distinguished career.

Edward Lucie-Smith

Chronology

-

A Battle (for the Partisans)

-

Sphere within a Sphere

-

Sphere within a Sphere

-

Four Steles

-

The Phantom of Cagliostro

-

Pomodoro in his studio