The 9th

LaureateArchitecture

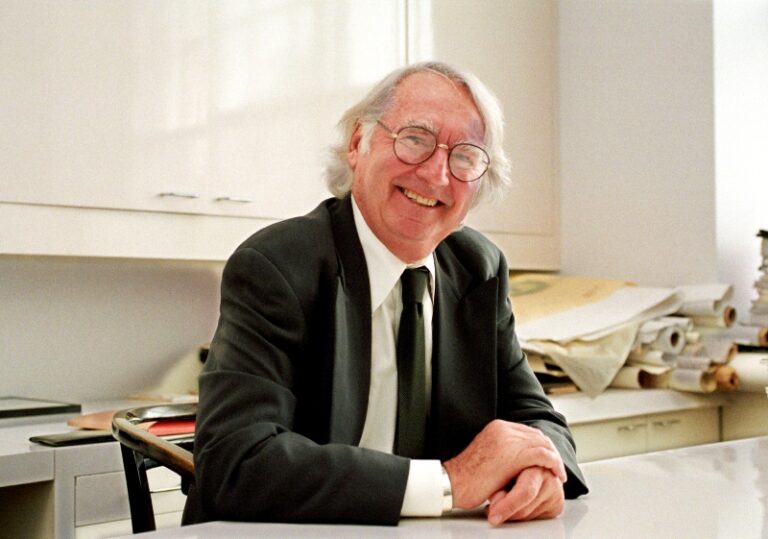

Richard Meier

Richard Meier’s first major work, the cubistic Smith House in Darien, Connecticut, announced at the same time both his dominant formal syntax – orthogonality – and his preoccupation with white. From private housing he progressed to public facilities, such as the Bronx Developmental Center of 1977, and on to the museum architecture for which he is renowned. Buildings such as the High Museum in Atlanta, the Museum of Contemporary Arts in Barcelona and the City Hall in The Hague, Holland, show the cool literacy of Meier’s mature style, while a building such as the Getty Center in Los Angeles is a tour de force of designing within a complex cultural framework. No other contemporary American architect has produced such consistent civic work or responded to existing urban fabric in such a responsible and modulated way.

Biography

Notorious for being obsessed with white, Richard Meier first came to public notice with his cubistic Smith House completed at Darien, Connecticut in 1967. There followed a sequence of similar neo-Corbusian houses built out of standard stud framing, sheet rock and timber cladding, and painted white inside and out. This line culminated in the spectacular Douglas House of 1973, erected on a wooded, cliff-top site overlooking Lake Michigan. At this time Meier began to widen the scope of his practice, not only by realising a number of public commissions, but also by veering away from his monochromatic palette and cubistic syntax. These new directions were particularly evident in his Twin Parks housing complex in the Bronx of 1974, faced throughout in dark brown blockwork.

Another form of revetment was adopted in his Bronx Developmental Center, completed in the Bronx, New York in 1977 – a therapeutic-educational facility for handicapped children, clad throughout in aluminium panelling. Paradoxically, this led him back to his proverbial white finish, apparently through the efficacy of the aluminium panels employed in the Bronx. These panels suggested the use of white enamelled steel cladding for Meier’s next commission; a treatment that was destined to become a permanent feature of his architecture over the next 20 years. Subject to the influence of the eighteenth-century German Baroque architect Balthasar Neumann, this radiant finish was initially integrated into Meier’s own ‘baroque’ aesthetic in The Athenaeum reception center, built in 1979 on the site of the nineteenth-century utopian community of New Harmony, Indiana. With its multiple access ramps, bulbous undulating walls, sculptural escape stairs, tubular steel handrails, free-floating, disjunctive planes and white steel panelling, The Athenaeum inaugurated Meier’s civic syntax, a language which would be elaborated in one public building after another over the next decade. This phase began in 1983 with the Frankfurt Museum of Decorative Arts and the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia, and culminated, as far as his European practice was concerned, in such prominent cultural institutions as the Canal Plus Television Headquarters in Paris, 1992; the Städthaus Ulm; The Hague City Hall and the Museum of Contemporary Arts in Barcelona, all dating from 1995. These works established Meier’s reputation as being the most ‘European’ of his generation of American architects, particularly since, with the exception of the High Museum, he did not realise any works of comparable stature in the USA until the late 1990s.

This national neglect would be more than compensated by the 1997 Getty Center for the Arts and Humanities, erected on a scrub-covered natural acropolis in Los Angeles. In this rambling complex, Meier’s preference for an all-white finish was finally mediated by public opinion, causing him to face extensive sections of the complex in split travertine, with off-white enamelled metal panels complementing this stone-cladding elsewhere. Apart from its architectural attributes, the Getty Center confirmed Meier’s ability as an urban designer-cum-landscapist; a talent which had already become evident in a number of corporate campuses projected for European cities, including the expansion of the Renault administration facility in the Boulogne-Billancourt district of Paris, 1981, and an addition to the existing Siemens headquarters, projected for the centre of Munich in 1983.

A city-in-miniature rather than merely a building, the City Hall and Library in The Hague, completed in 1995, represents Meier at his civic and architectonic best. Here he went far beyond brilliant exercises in style – so far as to advance a specific sociocultural policy. Derived from the form of the nineteenth-century mega-galleria, Meier’s City Hall was an attempt to respond to the scale of the office buildings that had progressively overwhelmed the low-rise centre of The Hague during the previous decade. The architect attempted to compensate for this condition by creating a top-lit res publica, consisting of municipal offices stacked on either side of a galleria. Apart from providing office space, this galleria also accommodated a café terrace, a wedding room and a council chamber in addition to the cylindrical city library itself, which functioned as a civic threshold for the whole complex. Finished throughout in white panels, the galleria also served as a light-modulator in which the ever-changing angle of the sun, together with fluctuations in the weather, had an immediate impact on the pattern of light and shade and on the overall radiance of the interior.

Here as elsewhere, Meier’s key contribution is as much topographic as it is architectural. One notes that all of his public buildings have been brilliantly integrated into the urban context in which they are situated. There is in fact no other contemporary American architect who has produced such a consistent body of civic work or who has responded to existing urban fabric in such a responsible and modulated way.

Kenneth Frampton

Chronology

-

Smith House

-

Douglas House

-

Getty Center for the Arts and Humanities

-

Getty Center for the Arts and Humanities

-

Getty Center for the Arts and Humanities