The 12th

LaureatePainting

Ellsworth Kelly

Ellsworth Kelly is a grand master of abstraction,justifying the extreme economy of his painterly means not by theory or ideology but simply as the abstract confirmation of something seen in the real world. The flatness of his surfaces,the clarity of his compositions and the dispassionate manner of their execution suggested roots in the work of Mondrian and Arp; Kelly’s early works were certainly precursors of the minimalism that would flourish in the US in the mid-1960s. The influence of Calder may have encouraged him to work in three dimensions,yet Kelly’s pieces remained static,implying that the motion is created by the viewer. This subtle insertion of the concept of time into the experience of a work is yet another example of the extent to which the deepest existential concerns can be framed through art of the most minimal means.

Biography

The boy naturalist,alert to how Audubon and others made memorable portaits of living nature,became a student of the applied arts and then a soldier trained in camouflage and in making silkscreen prints. Only then could he pursue the career of a painter,studying in Boston and in Paris,and making his first free essays. Art history stored his mind and sketchbooks with suggestions ranging from Byzantine and Romanesque formalities to Matisse’s decorative aplomb. It was this that brought him to Paris in 1948 when other novices chose New York where the ‘New American Painting’ was surfacing. By the time he returned – he shipped himself to New York in 1954 – Abstract Expressionism had triumphed so decisively that rebel factions were forming against it,such as that of Johns and Rauschenberg.

Ellsworth Kelly always seemed designed by fate to make art simple and strong,not for personal display. Letting his eyes feed on all sorts of visual offerings,he painted and sometimes constructed succinct works that could have made him the father of minimalism and a key figure in the post-painterly abstraction group,promoting the essential economy of painting – flatness,clarity,dispassion – both born in the mid-1960s. Kelly took years to develop ideas from tiny sketches into large paintings and subsequently also sculptures. His first New York shows,in 1956 and 1957,presented mature achievement. Its assured character suggested such forerunners as Mondrian and Arp,but even then Kelly’s art did not call on ideas for justification,only its own abstract confirmation of something seen in the real world. This directness has kept him aloof from contemporary groupings. He had friends among the New York artists,but few of these shared his focus on the purely visual.

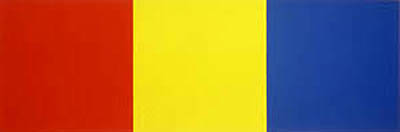

During the 1960s he made abstract paintings in a wide range of acutely adjusted colours,including black and white,on large canvases but sometimes also on small canvases or boards joined or grouped together to make one composite work. His colour areas were almost always squares or rectangles. Visual phenomena catch his attention and are held in sketches or photographs,from light on water to patterns of shadows on a wall,a girl’s scarf or a glimpse of typography,to be developed slowly and to perfection. Alexander Calder was one of the first to have recognized Kelly’s power,and may have encouraged Kelly to work three-dimensionally. From 1959 on he painted sometimes on sheet aluminium,angled to be freestanding. He did not make mobiles,in which visual tensions would be sacrificed to motion. Looking has its own dynamics,and a n used curved areas in his paintings – curves from nature and curves from manmade sights - in the early 1970s he began to make long,slowly curving divisions within paintings,then panels with curved sides,and then metal sculpture with almost imperceptibly curving silhouettes. Thus without yielding up any of the finality of his surfaces,he invited us to experience movement and time as our eyes read the outlines of his often large,drawn-out works. He also now overlapped two panels of discrete colours,an arrangement that can suggest succession and,more obviously,space even if their physical depth is no more than a few centimetres.

Kelly’s own statements have the same finality,avoiding all reference to personal states or preferences. We may discover these in the works themselves. Critics have found it hard to say anything general about them that fits the case. One fine instance is Mark Rosenthal’s remark that the adjustments required by Kelly’s work come from ‘a kind of perfect pitch’. The musical analogy confirms one’s experience of recent Kellys,in which colour announces a particular note,and the extent of it,its curvilinear or other shaping,affects timbre and duration. It follows that Kelly is very concerned with the display of his panels,as though searching for the perfect acoustical performance.

Norbert Lynton

Chronology

-

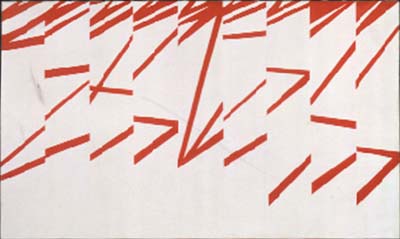

La Combe, 1950, 96.5 x 161.3cm

-

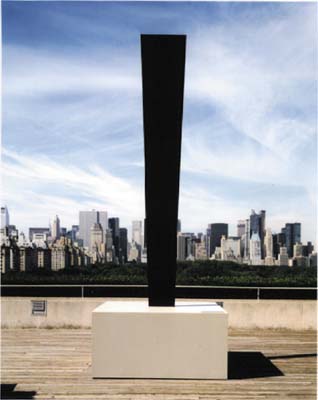

Sculpture for a Large Wall, 1957

-

Totem (for Roy Lichtenstein), 1991

-

Red Yellow Blue, 165.1 x495.3 cm

-

Installation View

-

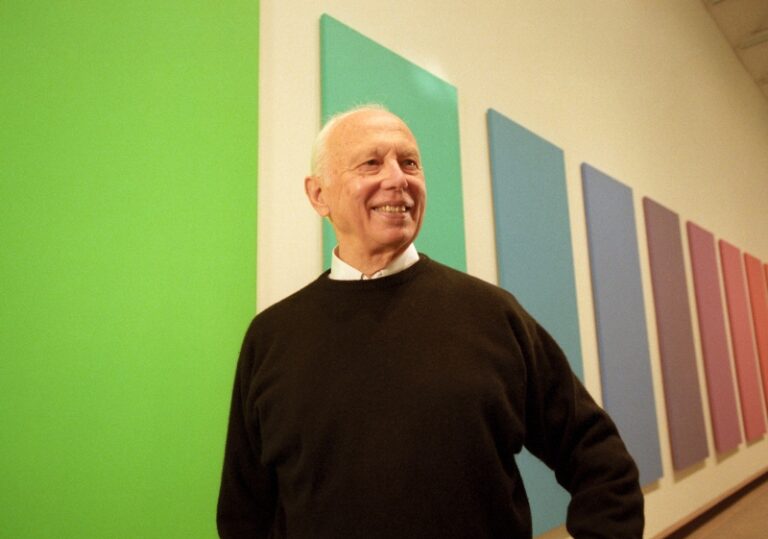

In front of his work

-

In front of his work