The 12th

LaureateMusic

Hans Werner Henze

Political commitment has provided Hans Werner Henze with a great motivation. His rejection of fascism and embracing of revolutionary socialism led to a musical language that combined experimentalism and popular song,opera and electronics,romantic style and spiky serialism. Often such oppositions play themselves out in a theatrical manner,providing either an explicit or programmatic drama which seems to convey great meaning. Henze’s music has included some of the most important symphonies and chamber works of the twentieth century,but also some highly varied pieces of music theatre. Most of all,the influence of the human voice is present in all aspects of his writing,be it for instruments or indeed voices. He afraid of neither complexity nor simplicity.

Biography

During a television interview in 1990,Hans Werner Henze spoke of his childhood in the Hitler Youth Movement and remembered how he heard his father and his drunken cronies singing in the woods. They sang of shedding the blood of Jews. It was a powerful moment of revelation,not just of the life and motivation of this complex composer,but also of the extent to which song and musical meaning are at the heart of his work. When,in 1953,Henze relocated from Germany to Italy,he rapidly absorbed an Italian sense of melodic line,even of bel canto,which led to his celebrated description of himself as ‘a north German contrapuntal temperament projected into the arioso south’. But the link with the voice goes much deeper than just a tendency to a lyrical style. In a large number of his compositions,Henze sets a text,then removes the words,leaving the resulting melody alone to ‘speak ’ its hidden meaning. Layering such melodies,and indeed textures,timbres,and rhythms,is the essence of his compositional technique,as a drama of musical and extra-musical meanings is played out both behind and within the musical surface.

This technique is a consistent characteristic of what has otherwise been an extremely varied career. As with many of his contemporaries,Henze embraced first neoclassicism and then serialism in his early years. However these orthodoxies were rapidly subverted by an overt lyricism,then experimentalism,then political engagement. It is remarkable that a composer so known for his radical commitments should also be one of the most respected symphonists of our time,and yet the diversity of Henze’s output seems to allow for such apparent contradictions. At any rate,he continues to work within the classical tradition,whilst having done as much as anybody postwar to extend or even rupture its boundaries. So,in 1976,his ‘actions for music’,We Come to the River used a text by Edward Bond and all manner of experimental devices,including graphic notation,improvisation and electronic techniques,in a dramatization of class conflict which explored the potential of music for political statement. Yet in the following year he composed the Aria de la folía española for chamber orchestra,which was a much more conventional work,reinterpreting traditional styles in a lyrical style.

With such an emphasis on text,drama and the voice,it is not surprising that he has written more than forty operas and ballets. The most celebrated of these are probably: The Bassarids,1966,a reworking by W H Auden of The Bacchae,and a piece which marked the start of Henze’s political activism; and The English Cat,1983,which follows a traditional sequence of individual ‘numbers’,owing a great deal to Monteverdi and the ensuing tradition of opera. However,it is the ‘core’ works of the classical composer,the symphonies and string quartets,which provide perhaps the best narrative of his compositional evolution. Thus one can compare the angular writing of the Sixth Symphony,1969,composed in Cuba and incorporating political songs,with the Seventh Symphony,1983–84,in which Henze seems to make a rapprochement with the German Romantic tradition.

The last two decades have seen a development of the latter tendency and an increase in the more personal expressive aspects of Henze’s style. A good example of this is the instrumental Requiem,1990–91,which was a response to the death of Michael Vyner,the former director of the London Sinfonietta. This is a set of nine ‘spiritual concertos’ for solo piano,concertante trumpet and chamber orchestra. The construction of the piece owes something to the 17th-century German composer Heinrich Schütz,and there is an evident awareness of the tradition of requiem mass settings,although Henze himself is not a Catholic. The strongest impression left by the music,however,is of a deep personal anger at the untimely death of a friend,and it is this personal character which makes Henze’s recent work speak so well to audiences. With typical invention,the choral Ninth Symphony,1997,develops this language in its turn to explore familiar political themes,in this case Fascism. The same themes: myth and narrative,politics and personal expression,modernism and popular feeling,saturate Henze's work throughout his career. His ability to synthesise both complementary and conflicting ideas and his apparent relish of the complexity and difficulty that this can produce,has meant that he remains a vital force in Western music.

Andrew Hugill

Chronology

-

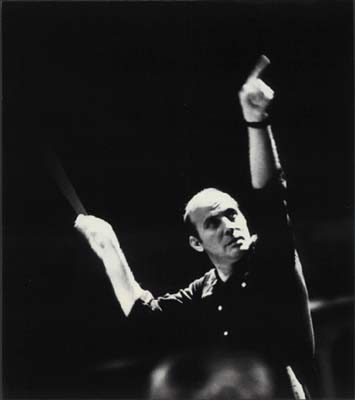

Henze Conducting, 1971

-

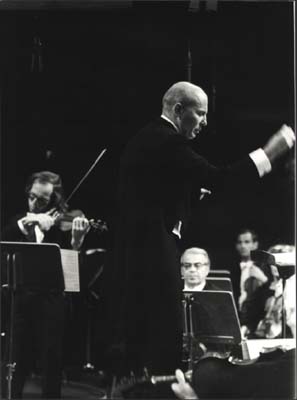

Henze with Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, 1976

-

With Gidon Kremer, 1979

-

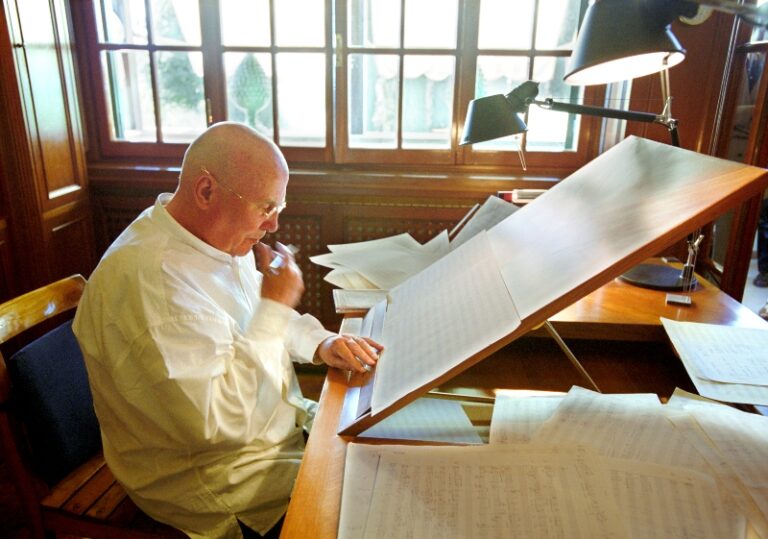

At his home

-

At his home

-

At his home