The 3rd

LaureateSculpture

Eduardo Chillida

Eduardo Chillida was goalkeeper for Real Sociedad in the early 1940s; there is a relationship between that and sculpture,he says: ‘You must have a very good connection,in both professions,with time and with space.’ His sculptural work is massive and monumental; Chillida is a manipulator of space,and through that of the viewer’s sense of time. Influenced perhaps as much by the grey skies of his native Basque region as by classical sculpture,works such as Peine del Vento in San Sebastian,its claw-like protrusions eating hungrily into the coastal space,established Chillida as Spain’s foremost sculptor. Working in a variety of heavy materials such as concrete,steel and wood,Chillida continues to expand his sculptural vocabulary and to grapple with space and time.

Biography

Although Eduardo Chillida works with massive materials,and often on a very large scale,he sees himself as being primarily a manipulator of space,and,through his manipulation of space,of the spectator’s sense of time or duration. It is an appealing part of his legend that he was once goalkeeper for the Real Sociedad football club in San Sebastián,which then,as now,ranked highly in the Spanish league. Chillida once remarked that he saw a close connection between being a sculptor and keeping goal: ‘You must have a very good connection,in both professions,with time and with space’. Some of his fellow citizens in San Sebastián apparently still know him better as a former goalkeeper than as a modern sculptor.

It has been customary to speak of Chillida as a direct descendant of Julio González,taking over from him the Spanish artisan tradition of working in forged iron,and turning it to new modernist uses. Such an interpretation,though,ignores the wide range of materials and techniques that Chillida has used throughout his career. His earliest sculptures,for example,were in stone and in plaster,and he has also made work on a monumental scale in wood and concrete. It is similarly misleading to think of him as being a sculptor whose influences are primarily from the Mediterranean world; he has spoken of the typically grey overcast skies of his native region,which borders on the Atlantic. At first he consciously avoided looking at Greek sculpture but was finally drawn to it when he had an accidental encounter with a Greek fragment when visiting the Louvre – the detached,broken hand of the Victory of Samothrace. Perhaps part of its appeal to him was that,although he is an abstract sculptor,he has long made a practice of drawing hands,chiefly his own. His encounter with the marble hand in the Louvre prompted him to travel to Greece in 1963,a visit that led to a considerable lightening in the mood of his work.

Chillida has,in the course of his career,undertaken a large number of public commissions. The success of these commissions depends largely on his response to the site. When he is seized by an idea it is likely to take the form of a spatial paradox. Some of his most typical sculptures are concerned with the projection of mass into space and often take the form of large iron slabs,pierced with openings of different shapes and sizes,and supported a short distance from the ground on three simple legs. Chillida says he liked the idea that the real sculpture was the space you perceived through the slab,but that he also wanted this space to be limited in some way,not stretching out into the infinite,as it would have been if the slab were raised and placed against the sky.

Chillida’s position as the leading Spanish sculptor of the last 50 years has been affected by the way in which his Spanish predecessors,Picasso and Julio González,expatriated themselves to France,abandoning Spain and becoming part of the international modern movement. Chillida had moved to Paris in 1948,only to ‘discover the importance of being a Basque’; by 1951 he had returned to Spain. It is in the heart of the Basque region,close to San Sebastián,that his best known work,Peine del Viento XV (‘Comb of the Wind’),1976,is sited. The sculpture’s massive steel forms clasp and frame the rugged Basque landscape,but it is the space between these forms,the suggested rush of air even on calm days,which gives the piece its vitality,as the title itself suggests.

It is certainly possible to see in Chillida’s sculptures a relationship to the kind of painting produced at the same time by Antoni Tàpies and the other artists who based themselves on another region with a strong separatist tradition,Catalonia. Like them,he used an abstract vocabulary to express resistance to the centralism which prevailed under the Franco regime. But in some ways he carried this resistance even further than his Catalan colleagues,since his more ambitious sculptures are public works. Spanish conservatives were right to find in them something subtly subversive,though his critics could not always pin down precisely what this was.

Nevertheless,Chillida is,primarily,an intuitive sculptor. He is as deeply resistant to any form of stylistic classification as he is committed to expanding his sculptural vocabulary; he has described his creative process as follows: ‘Finally,when I am working,I am questioning the unknown. This is my real problem. I work to know; my work is a problem of knowledge. Knowledge is something in the past; to know is something in the future.’

Edward Lucie-Smith

Died August 19,San Sebastian,Spain

Chronology

-

Peine del Viento XV

-

Peine del Viento XV

-

Mr. and Mrs. Chillida

-

In front of his work

-

Chillida's metal foundry

-

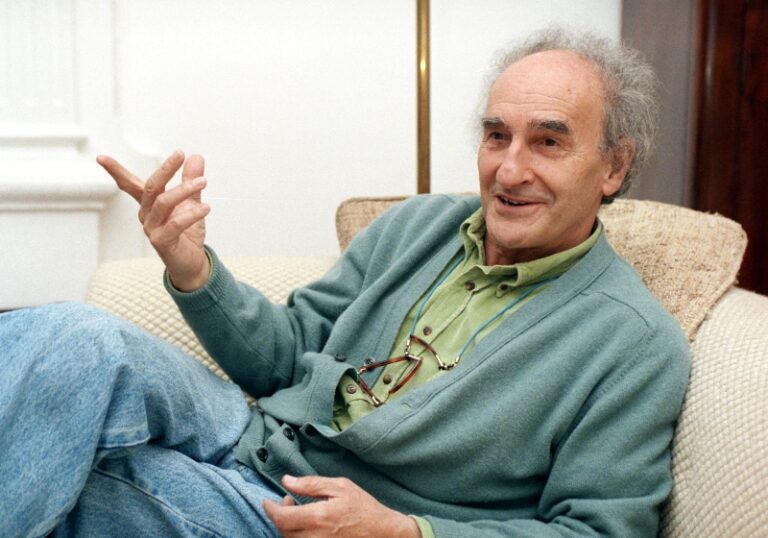

Eduardo Chillida in his studio