The 9th

LaureateTheatre/ Film

Peter Brook

Peter Brook is widely recognised as one of the world’s finest theatrical directors. Throughout his long and prolific professional life,the defining constants of his theatrical (and cinematic) productions have been their craftsmanlike quality,luminous intelligence and sheer unpredictability. Tireless interpreter of Shakespeare,explorer of theatre in different parts of the world,expert adaptor of contemporary work,Brook has always appeared to be in quest of two things: the heart of meaning in human communication,and the heart of theatre itself. This almost spiritual element to his work has never obscured his eye for theatrical effectiveness. The American critic Mel Gussow once described him as ‘part-shaman,part-showman’. With Peter Brook,the two halves are seamlessly fused.

Biography

It is often the fate of an iconoclast to find his status ultimately elevated to that of icon; as it is often the fate of an innovator to discover to his frustration that his pioneering achievements have been consolidated,refined and overtaken by disciples and outright imitators. The first half of that statement is true of Peter Brook,now widely recognised as one of the world’s finest theatrical directors. The second,by contrast,does not apply since,instead of resting on his laurels (which in his case have turned out to be the hardiest of perennials),Brook has consistently outpaced the Young Turks who took their cue from him. To use an obsolete political expression,what Brook brought to the theatre is the concept of permanent revolution.

A simpler way of saying much the same thing is that,throughout his long and prolific professional life,the defining constant of his theatrical (and cinematic) productions has been their sheer unpredictability. Brook,in short,is an artist impossible to second-guess – or even to first-guess. Just as,for example,it appeared possible to pigeonhole him as a tireless interpreter of Shakespeare at both Stratford-upon-Avon and the National Theatre in London,he would turn his attention to such contemporary works as Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge and Jean Anouilh’s Ring Round the Moon. Just as he mapped out a space for himself as an explorer of the oblique relationship between art,science and memory with The Man Who,a mesmerising drama which drew its inspiration from the neurologist Oliver Sacks’ classic collection of case-histories The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,he confounded his admirers with a seven-hour dramatisation of one of the most ancient and epic of Indian legends,The Mahabharata. And,even if established as a mainstream opera director,he tackled one of the creakiest warhorses of the entire operatic repertoire,Bizet’s Carmen,by pruning away all the clichés,the garishly folksy folderols,of pseudo-Spanish local colour which over the years had tenaciously attached themselves to the work the better to expose the stark,sun-bleached aridities of Merimée’s original novella. Consistently reinventing himself,he has epitomised the artist as someone whose role is to pose all the right questions rather than deliver all the right answers. As he himself phrased it,‘Not knowing is not resignation. It is an opening to amazement.’

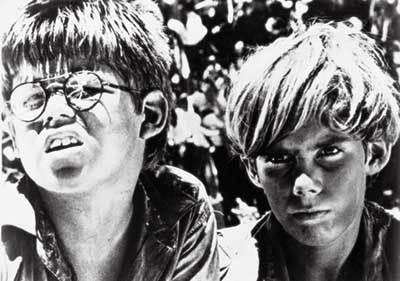

Brook’s career in the cinema,though intermittent – his primary commitment has always been to the theatre – has been no less startlingly eclectic,each film in the canon contradicting,in its style,theme and even visual texture,the one preceding it. Launching himself with a jubilant Technicolor adaptation of John Gay’s earthy,street-ballad ‘musical’ The Beggar’s Opera,he followed that with an austere,monochrome,uncannily ‘French’ film,an adaptation of Marguerite Duras’s Moderato Cantabile starring a youthful Jean-Paul Belmondo. Then with a memorable low-budget version of William Golding’s macabre allegory Lord of the Flies (still his best-known film),its cast composed almost entirely of young boys. Then,in the eighties,and maybe most unexpectedly of all,with Meetings with Remarkable Men,a weird and colourful account of the peregrinations of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff,a mind-expanding spiritualist to some,an out-and-out charlatan to others. On film,Brook’s concern has therefore been above all,and perpetually,to change the subject.

Another of his abiding preoccupations has been an interest in the restless,endlessly shifting interaction of a live production and a live audience,an interaction which can of course be meaningful only in the theatre. His film version of King Lear,with Paul Scofield in the title role,was a useful record of a pre-existent stage production: watching the blazingly memorable production itself,one felt as though a cataract had been removed from the text. Similarly,Brook’s film of the celebrated Marat-Sade – or,to grant it its extravagantly full title,The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat,as performed by the inmates of the Asylum of Charenton,under the direction of the Marquis de Sade – was an intelligent but arguably foredoomed attempt to transpose a work of art from one medium to another,whereas the original stage production,one of the emblematic highlights of British culture in the sixties,was so indelible it has rendered the play itself,emancipated from Brook’s mise-en-scène,virtually unrevivable. And it is significant that he never sought to film his unforgettable circus-inspired re-interpretation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream,dependent as it was it on an exclusively theatrical illusion of wonder and enchantment.

The American critic Mel Gussow once described him,in an arresting phrase,as ‘part-shaman,part-showman’. Yet Gussow himself was only part-right. With Peter Brook,the two halves are seamlessly fused. The medium is the message,the shaman is the showman.

Gilbert Adair

Chronology

Tony Award for production of Marat/Sade

Journey in Africa.

Orghast,Festival of Persepolis,Iran

Tragedy of Carmen (opera,Lincoln Centre,New York)

-

Lord of the Flies

-

Oh Les Beaux Jours, 1997

-

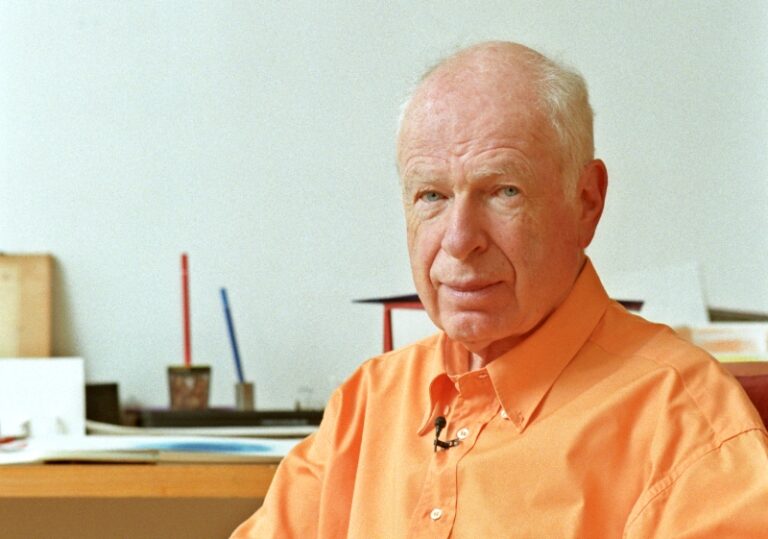

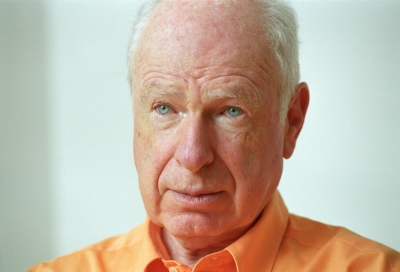

At his studio

-

At his studio