The 11th

LaureateSculpture

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois is recognised around the world as an artist of outstanding quality and troubling vividness. The deaths of her parents and husband influenced her work massively, as had her parents' occupations: owning a gallery specialising in historical tapestries and directing New York’s Museum of Primitive Art. Bourgeois pursued a kind of metaphorical expression with shocking vigour, incorporating her own clothes and diverse materials as well as carved and modelled forms in room-like installations often suggesting claustrophobic, forbidding bedrooms. Some of her fetishistic pieces become anthropomorphic, others ghastly encounters; there is no innocence in her world, no childhood, no unadulterated dream. Yet her final purpose is constructive: we all live merely human lives, she seems to be saying, and we must learn to forgive ourselves, even for that.

Biography

Louise Bourgeois’s first shows, in 1939 and 1945, were of etchings and paintings. After studying mathematics and philosophy she had got her art training at a number of Paris studios, including that of Léger, before moving to New York in 1938 as the bride of the American art historian Robert Goldwater. Born in Paris on Christmas Day 1911, she had grown up in a well-to-do Paris household. Her parents owned a prominent tapestry gallery. Louise learned from her mother the stitch-by-stitch restoring of old tapestries, and also their bowdlerisation to fit customers’ tastes. Glimpses or fantasies of her parents’ sex lives were heightened by awareness that her tutor was her father’s live-in mistress and of his general promiscuity, while a lavish supply of couturier clothing bred her to be body and fashion-conscious beyond the norm. In her thirties, her hair hung down to her hips. Her husband, expert on modernism’s debts to tribal artifacts, was director of New York’s Museum of Primitive Art.

Bourgeois extended her studies at the Art Students’ League, but now turned to sculpture, exhibiting her first wood carvings in 1947. She expanded her work, turning to marble and bronze in the 1960s, and became a conscious feminist. Her father’s death in 1951 had been a key moment in her personal history; another was her husband’s death in 1973, just as she was becoming known as a sculptor. Soon she would be receiving academic and national honours in the USA and in France, and establishing herself as a very particular artist with such works as The Destruction of the Father, 1974, and her installation sculpture Confrontation associated with a performance piece she called A Banquet, a Fashion Show of Body Parts, both 1978. In 1982 the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented a major retrospective of her work; another such was shown in Paris in 1995. In 1993 her work filled the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

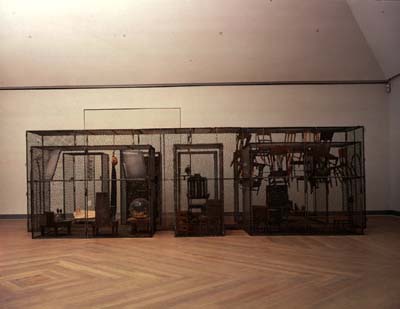

By this time she was recognized around the world as an artist of outstanding quality and troubling vividness. Her prime subject, she has said, are the traumas she suffered in girlhood. Her mother’s death in 1932 removed a protective figure between herself and her loved and hated father. Memories of what she experienced and what she imagined have been the mental source-material for her art; personal possessions reflecting that past have enriched its delivery at a time when painting too sometimes incorporated objects in the manner of relics. Such a headlong pursuit of metaphorical expression was unknown in sculpture, however – in spite of the Surrealists’ interest in ‘disagreeable objects’. Pursued by her with such persistence, her sculpture became fetishistic – encouraged by her familiary with primitive art – so that added to modelled and carved forms the use of latex, plastic, cloth and welded steel as well as her own clothes, recycled as symbolical presences in ‘cells’, as she calls her room-like installations, often suggesting forbidden, claustrophobic bedrooms, and in her untitled free-standing clusters of objects supported by poles in which clothes and suggestive objects made from cloth, together with in one case a massive anthropomorphosed treeroot, in another animals bones serving as hangers, confront our half-resistant, half-comprehending minds. So there is no innocence, no childhood, no unadulterated dream, no hope of escaping an animality that injures us only because we give so much to pretending it isn’t there.

A small, fragile woman, Bourgeois has waged war on her family name and against the idea that the arts exist to screen us from truth. Not everything she has made arraigns her past, but her benign images offer us little comfort. The spiders she has made since 1995 represent the caring, safeguarding mother at the centre of the web which was Louise’s childhood world. They are ghastly encounters in themselves, more recently accompanied by other things demonstrating their benign roles. Spiders devour mosquitoes; mosquitoes bring malaria and, some say, AIDS; Louise’s three children needed protecting against them. There is love in her art, but there are also headless, limbless torsoes forever linked in lust – made in cloth and crudely stuffed. Breasts may be a blessing but endless multiple breasts, as in The Destruction of the Father and in the latex costume she made and wore a year later in parody image of emblematic Charity, mock the mindless worship of feminine charms in life and in art. Her notebooks swarm with acute words that guide art-critical commentaries and cast light on her imagery, and also little drawings that needle their way into our reluctant consciousness with their epigrammatic symbols of entrapment and abuse.

The power of her work to dismay, at the very least, and to spread awareness is clear. Growing familiarity with her work suggests that Louise Bourgeois’s overarching purpose is positive and constructive as well as self-reconstructive: we all live merely human lives, and must learn to forgive ourselves even for that.

Norbert Lynton

She passed away on May 31, 2010, New York

Chronology

-

Bourgeois at home

-

Bourgeois at home

-

Sleeping Figure, 1950

-

Janus Fleuri, 1968

-

Passage Dangereauz, 1977

-

Arch of Hysteria, 1993

-

Spider, 1997