The 3rd

LaureateTheatre/ Film

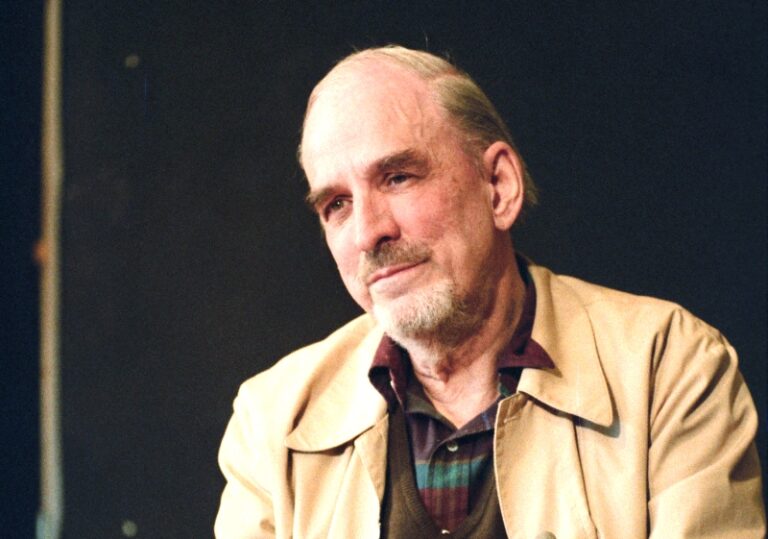

Ingmar Bergman

Ingmar Bergman’s stature as one of the medium’s finest directors has never been questioned. His reputation was consolidated in 1955 with a Special Jury Prize at Cannes for Smiles of a Summer Night,an elegantly rococo comedy of manners described by critics with the for once not abused epithet ‘Mozartian’. Two years later The Seventh Seal,perhaps the director’s most famous work,was released. It was Bergman’s Faust. For several years Bergman alternated between comedies and dramas,a versatility which tended to be forgotten in his later career,when his natural pessimism became the (caricatural) public perception of his sensibility. During this period,nonetheless,a series of profoundly uningratiating films established Bergman as perhaps the best-known art-cinema director in the world.

Biography

One of the planet’s most glamorous if frustratingly elusive natural phenomena,visible only against a cloudless night sky,is the fabled green ray,the ultimate beam to be flashed forth by a setting sun before it dips over the horizon. Many a late work in a filmmaker’s career resembles that ray: a work,for example,like Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander,made in 1982,in the director’s sixty-fourth year. Even if Bergman has continued to work intermittently,mostly for television,Fanny and Alexander was his true adieu to the cinema,a gorgeous sunset,stuffed to the brim with all his tics and characteristics,his stylistic and thematic obsessions,yet also imbued with a valedictory warmth reminiscent of his earliest comedies,a green ray of filmic poetry from a director whose stature as one of the medium’s finest has never been questioned.

His reputation was consolidated in 1955 with a Special Jury Prize at Cannes for Smiles of a Summer Night,an elegantly rococo comedy of manners (of bad manners),a Bergmanesque bergamasque described by every critic in the world with the overused and for once not abused epithet ‘Mozartian’. Then two years later The Seventh Seal appeared. Still perhaps the director’s most famous work,a medieval allegory of life,death and redemption,it was Bergman’s Faust; and the emblematic image of Max von Sydow,a prominent figure in the filmmaker’s growing repertory company,playing chess with a cowl-hooded Devil is still one of the most potent in the medium’s iconography,ubiquitous to this very day in albums,dictionaries and reference books.

Thereafter,for several years to come,Bergman alternated between comedies and dramas,a versatility which tended to be forgotten in his later career,when his natural pessimism,his enduring preoccupation with the meaningfulness,or not,of good and evil,morality and faith,in a world from which God,if He ever existed,has withdrawn in disgust,became the (caricatural) public perception of his sensibility. Such delightful films as Lesson in Love,The Devil’s Eye,Now About These Women (a stylised satire on the pesky critical establishment that had been snapping at his heels since his debut) and even his exquisite screen version of The Magic Flute all testify to an impish humour and humanity which have been overshadowed by the bleakness of much of his work,honeycombed as it is by both metaphysical self-questioning and physical self-laceration.

At least until the sixties,Bergman’s had been a flamboyant,even Gothic art,deeply influenced by the theatrical productions (Ibsen,Strindberg,Shakespeare) that he had never ceased to stage even after becoming an internationally celebrated film director. Many of his most admired efforts were period pieces: he was one of the very few filmmakers capable of recreating a plausible simulacrum of the Middle Ages,as in his drama of rural rape,The Virgin Spring; and his ornately prettified vision of nineteenth-century Sweden clearly derived from the French,German and Scandinavian neo-classical masterworks which he staged at the Royal National Theatre of Stockholm. Alternating with these were films whose generosity of emotion gave them wide popular appeal: notably,Wild Strawberries,1957,a study of the regrets,recriminations but also new-found serenities of approaching old age (it starred,in a superb performance,Victor Sjöström,himself once a great silent director) and Brink of Life,1958,a quasi-documentary portrait of three women in the final stages of pregnancy.

During the following two decades,however,Bergman purified his technique until each of his films appeared akin to that somewhat paradoxical artefact: an austere diamond. Having delivered himself of a few of the greatest symphonies (as it were) in film history,he turned to chamber music and produced what might be characterised as,in a not absurd comparison with Beethoven,a series of late quartets,genuinely haunting in all their angst-ridden jaggedness. These profoundly uningratiating films – the trilogy of Through a Glass Darkly,Winter Light,The Silence; Persona,a mesmerising study of the psychic transference of personality that is arguably his masterpiece; The Shame; The Passion of Anna; and the visually splendiferous Cries and Whispers (whose unexpected popular success,according to Truffaut,was primarily due to its blood-red sets) – made Bergman perhaps the best-known art-cinema director in the world.

There remained the very last works of this apparently indefatigable creator of forms who,having publicly bid farewell to film with Fanny and Alexander,was incapable of remaining inactive even right into his eighties. Though filmed for television,and in somewhat straitened circumstances,such works as After the Rehearsal and In the Presence of a Clown testified to the undimmed brilliance of the cold Nordic light that had illuminated the cinema for half a century. The old master had,in short,more than one green ray up his sleeve.

Gilbert Adair

Chronology

It Rains on Our Love

Sawdust and Tinsel

Wild Strawberries

-

The Seventh Seal, 1956

-

Autumn Sonata, 1978

-

©The Sankei Shimbun