The 5th

LaureateArchitecture

Kenzo Tange

Kenzo Tange’s first major work,the Corbusier-influenced Hiroshima Peace Centre of 1952,brought him immediate acclaim. His monumental concrete style culminated in works of exceptional originality and power at the end of the 1950s and the early 1960s. By the time he designed the magnificent stadia for the Tokyo Olympics in 1964,Tange had fully established a language that was both startlingly powerful and yet highly expressive. He was active too in the area of urban planning,having proposed a radical master plan for the development of Tokyo Bay in the early 1960s. Through his interdisciplinary team,URTEC,Tange continued to assert that there was no transformation that could not be effected through the application of technology,talent and political will,a belief that has continued to inform all his magisterial work to the present.

Biography

After serving an apprenticeship with the neo-Corbusian architect Kunio Maekawa,Kenzo Tange received immediate acclaim for his Hiroshima Peace Centre,a memorial park on the site of the first atomic bomb. The museum,the information centre,and the hyperbolic shell that is poised over the symbolic epicentre of the explosion are each essays in a monumental concrete manner for which he would soon become renowned. Following Maekawa’s lead,Tange evolved a type of anti-seismic,reinforced concrete construction that was capable of both incorporating the values of modernity and evoking the time-honoured national style of monumental timber building.

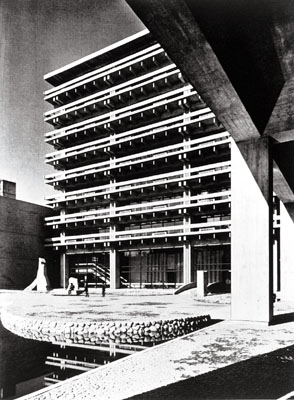

Tange developed his fair-faced concrete syntax in a series of institutional buildings that he realised during the 1950s as part of a national reconstruction programme,culminating in two works of exceptional originality and power – the 1958 Kagawa Prefectural Government Office in Takamatsu and the Kurashiki City Hall of 1960. Both works epitomised the wakonyonsai style,in which a concrete trabeated frame,cast in-situ from boarded formwork,was of such a proportion and rhythm as to recall traditional Japanese timber framing.

Tange’s architecture was not,however,restricted to trabeated form,as we may judge from his excursions into shell and folded-plate construction – first in the Shizuoka Hall,built near Fujiyama in 1957 and then in the Imbari City Hall of 1959 and the Nichinan Cultural Centre,Kyushu of 1962. With its inclined reinforced concrete walls and roofs the Nichinan Centre expanded the expressive range of concrete shell and folded plate construction,as this had first been developed by such engineers as Felix Candela and Pier Luigi Nervi. Splayed in plan yet still rationally organised,dynamically structured in spatial terms yet lit by small windows,this massive canted composition evoked a megalithic modernity. The Totsuka Golf Club,1963,and the Yoyogi Stadia for the Tokyo Olympics,1964,developed this highly expressive syntax further,particularly in the hyperbolic roof of the Olympic Stadium and its attendant circular arena. These were both steel cable structures suspended from concrete pylons which had been cast integrally with the concrete shells of the tribunes themselves.

Apart from realising what was then the largest cable-suspended roof in the world,Tange was at the peak of his powers in other respects; above all in the field of urban design. Confident that there was no urban transformation that could not be effected through the mutual application of technology,talent and political will,Tange assembled an interdisciplinary team known as URTEC. This group of architects,engineers,planners and economists first proved their capacity in Tange’s Tokyo Bay proposal of 1960,which adapted Le Corbusier’s Radiant City precepts of the 1930s to totally new circumstances. This project,which would prove to be the last comprehensive master plan of the twentieth century,would have entailed building an elevated autoroute system across Tokyo Bay with central office accommodation suspended above and residential megastructures situated to either side. Despite the fact that this ambitious scheme remained unrealised,it nonetheless formed the nucleus for Tange’s Tokaido Plan,projecting a vast megalopolis running down the entire length of the country.

On the strength of these propositions,URTEC was subsequently commissioned with a number of urban plans for different parts of the world,including Skopje,Yugoslavia,1965–66; Yerba Buena,San Francisco,USA,1967–69; Librino,Sicily,1971–76,and above all the Fiera district in Bologna that was finally completed in 1986 as the administration centre for the Emilia Romagna region. In many ways this was a further development of the megastructural potential that Tange had first demonstrated in his Yamanashi Region Communication Centre in Kofu,1967,featuring bridge-like office accommodation spanning between cylindrical service cores.

The high-tech world exhibition staged in Osaka in 1970,for which URTEC served as the coordinating architect,had the paradoxical effect of undermining the rational line in the Japanese modern movement. After Osaka,older and younger architects alike lost their confidence in the manifest destiny of techno-scientific progress and,subject to the influence of the Japanese metabolist movement (for whom Tange served as a kind of guru),Tange’s own method became progressively transformed. The heavyweight concrete syntax that he had evolved over the previous 20 years was gradually abandoned in favour of high-rise structures clad in faceted curtain walls of black glass,of which his Sogetsu building,completed in Tokyo in 1977,was one of the most sublime. URTEC resurfaced in Tange’s second proposal for an expansion of the capital into Tokyo Bay in 1986. On this occasion however,the generally low-rise,high-density profile was much more pragmatic,suggesting that Tange had been compelled by pluralist,democratic process to review his role as form-maker to the post-industrial age.

Kenneth Frampton

He passed away on March 22,2005,Tokyo

Chronology

-

Hiroshima Peace Centre

-

Kagawa Prefectural Government Office

-

National Gymnasium for the Olympic Games,

-

National Gymnasium for the Olympic Games,

-

Fiera District Centre, Bologna

-

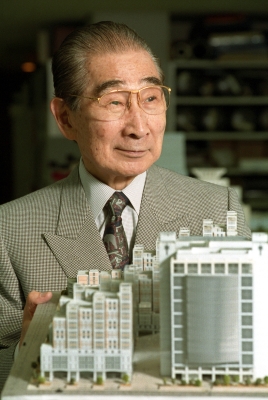

At his office

-

At his office