The 4th

LaureateMusic

Alfred Schnittke

The circumstances of Alfred Schnittke’s life were shockingly bleak. The Soviet authorities did their best to hamper his activities by preventing access to scores and recordings,making travel impossible and leaving him to live in a dingy three-room flat on the fifth floor of an apartment block miles outside Moscow. Despite this,and serious health problems,he produced a vast and highly influential body of film and concert music,and added the term ‘polystylism’ to the lexicon of compositional techniques. Many of Schnittke’s pieces contain quotation,semi-quotation,pastiche and stylistic references,combined in a fragmented yet meaningful way. At its most powerful,his music is highly intense and yet 'visual' or even cinematic in its sense of narrative.

Biography

The breadth of Alfred Schnittke’s music,the embrace of very different styles,themes and approaches in work of startling originality,is the manifestation of what he called ‘polystylism’. For Schnittke this was the result of an all-embracing enthusiasm: ‘I can only say that I like the whole of music. For me there is no music which exists today or music which existed 300 years ago. For me,music is the whole. So the connection between the different elements just goes on.’

Polystylism,defined as the use of a range of musical styles within a work,may at first glance seem like a recipe for postmodern whimsicality and kitsch,but in Schnittke’s hands it turned out to be firmly grounded in the central European modern tradition. Certain earlier European works shared his concerns for underlying structural unity,textuality and meaning,such as the ‘Mahler’ movement of Luciano Berio’s 1968 Sinfonia. As the leading exponent of Schnittke’s music,the violinist Gidon Kremer,has explained,polystylism is ‘not just a gimmick or a question of parody; it’s more a case of provoking something in us,challenging us to look at things differently. Even the “pleasing” quotations in Schnittke’s music could be interpreted as a sort of alarm,warning us of all the nonsense going on around us.’

Schnittke was born in Engels,capital of the former Volga Republic,in 1934,to a German journalist father and a mother who taught German. The family lived in Vienna for two formative years,during which time Schnittke became aware of the music of Mahler,Schoenberg and Webern. As a student at the Moscow Conservatoire,Schnittke was encouraged by Shostakovich and hailed as his natural successor,but his interest in European modernism grew in the early 1960s after a visit by Luigi Nono. He absorbed some of the serial techniques that were then emanating from Darmstadt with only limited access to source material. Schnittke also worked with found material: his Symphony No. 1,1969–72,makes a direct reference to Haydn’s Farewell Symphony,except in reverse. Players enter one by one and begin playing,until eventually the conductor is obliged to come in to impose order on the musical chaos. This idea is explored further in Moz-Art à la Haydn,1977,in which the musicians have to change places for the middle section and leave the stage gradually at the end,abandoning the conductor who continues to conduct for a few seconds.

Such theatrical ideas often underline the compositional procedures. In Moz-Art à la Haydn,for example,Schnittke applies a range of musical devices including augmented,diminished and polytonal canons,to a violin part which is the only remnant of Mozart’s music for a pantomime (KV 416d). The overlapping repetition of the melody by different voices becomes dissonant at times. Nevertheless,Schnittke’s handling of the complex counterpoint ensures that there is an underlying sense of order,however chaotic the musical surface appears. The same can also be said of what is perhaps his best-loved work,the Concerto Grosso No. 1,1977,scored for two solo violins,strings,continuo and amplified prepared piano (an instrument invented by John Cage),in which once again we hear a juxtaposition of fleeting passagework and cadences in an evocation of baroque courtly dances,set against massive dissonances,and polyrhythmic and polytonal textures.

Although there is a great deal of artifice in Schnittke’s music,it rarely sounds artificial. Perhaps his experience of writing for film (he composed 66 film scores) gave him the stylistic fluency and familiarity with collage techniques – akin to flashback,quick cuts,and multiple exposures – to unify his music. Schnittke himself has drawn a parallel with nature to describe his approach to composition: ‘One can sit for hours by the sea and experience the magical effect of the waves,but the sea never reveals its structure to us. Where does the wave begin? Where is the climax? Where does the next commence? Is it one wave or a collaboration between several,in different stages of development? All of these questions are unanswered and will always remain so.’ Although he said this in relation to Passacaglia,1979–80,it stands as a metaphor for all his compositions,and especially those written in later life when illness forced him to write as few notes as necessary to imply the musical structure,rather than to state it directly.

The circumstances of Schnittke’s life were shockingly bleak. Although he moved to Hamburg after the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1989,years of privation had already begun to take their toll on his body. In 1985 he had suffered the first in a series of strokes which eventually killed him in 1998; each stroke further impaired his ability to write,and by 1994 he had also lost the power of speech. In spite of this,the final decade of his life saw the completion of his last four symphonies,numerous concertos and other concert works,as well as two major operas. His work spoke eloquently for him. Sardonic,sometimes humorous,theatrical and deeply musical,it is among the most original music to have emerged from the former Soviet Union.

Andrew Hugill

Chronology

Moz-Art a la Haydn (Play on music for 2 violins,2 small string orchestras,double bass,and conductor)

Concerto for Viola

Awarded the Praemium Imperiale Prize for Music, Japan Art Association, Tokyo

Symphony No. 7

Concerto for Three (violin, viola, cello and orchestra)

Historia von D. Johann Fausten (opera)

-

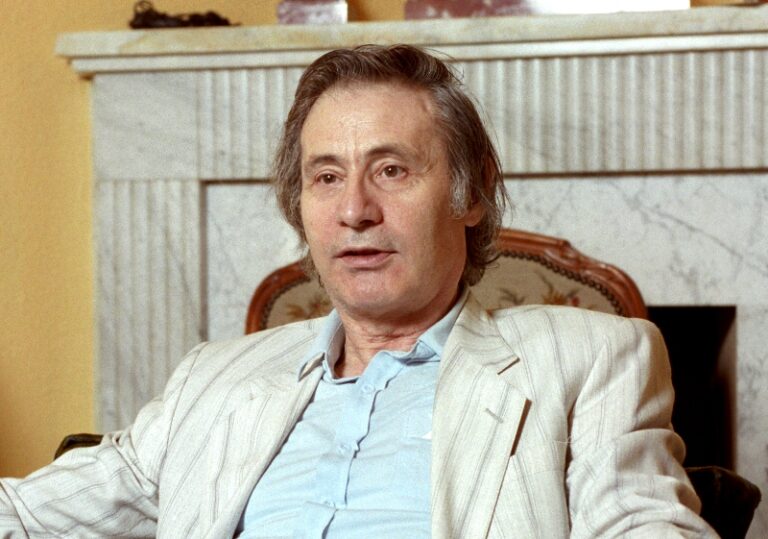

Alfred Schnittke and Gyorgy Ligeti

-

At his home

-

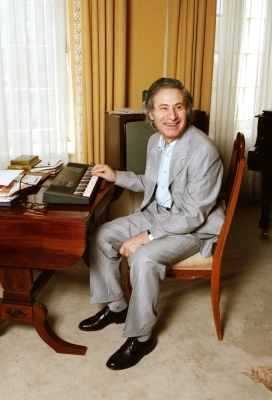

At his home

-

Schnittke and students