The 1st

LaureateSculpture

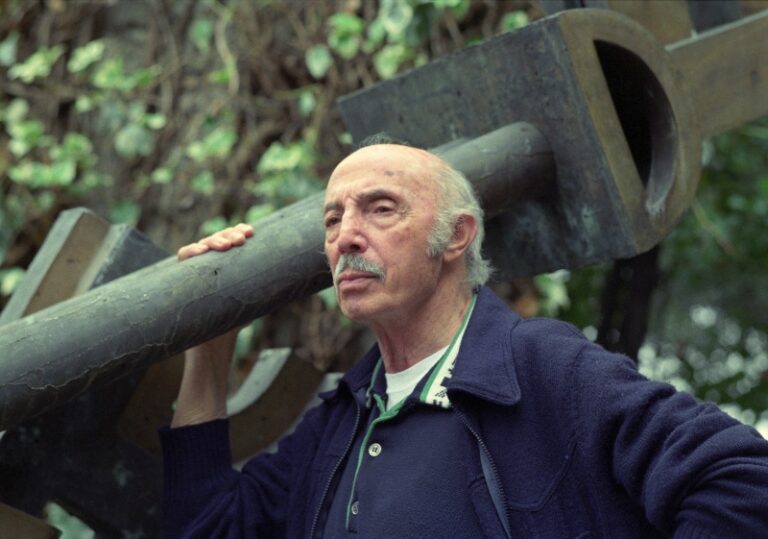

Umberto Mastroianni

Umberto Mastroianni deserted Mussolini’s army to fight alongside the Italian partisans against the fascists. War would become one of the major concerns of his sculpture,particularly that for public spaces. Several Italian cities are graced by monumental sculptures in honour of the Partigiani or the Resistenza: complex,apparently anguished explosions of form. From his pre-war,more classically-influenced sculpture his vision became increasingly abstract,taking influences from the futurist Boccioni and from the abstract expressionists. The sculpture became more mechanistic in appearance,alternating roughly worked surfaces with passages of smooth and defined form,without abandoning Mastroianni’s principal concern with graphically exposing the horror of war.

Biography

Umberto Mastroianni belonged to the generation of Italian artists whose careers were already well established in the 1930s. His earliest sculptural work is delicately figurative,in the tradition of late Etruscan art of the 4th and 3rd centuries BC that had also influenced a number of his exact contemporaries,artists such as Giacomo Manzù and Emilio Greco. In a more general sense,one can also see a current of influence from the French sculptor Aristide Maillol,whose work itself reflects the influence of the classical Mediterranean world and hovers between modernism and conservatism.

Although Italian art of the fascist period was not subject to the repressive measures that were inflicted on artists by the Nazis,the general cultural atmosphere of the time was cautious,with a strong bias towards classicism. During the Second World War,Mastroianni first fought in Mussolini’s army,before deserting to fight alongside the Italian partisans against the fascists. After the war he returned to sculpture with his Monumento al Partigiano (‘Partisan Monument’),1945,made for the Campo della Gloria in Turin. This continues the figurative direction his work had taken before the war; however,in keeping with its subject,it is much more anguished and expressive in style than his earlier work,in addition to being considerably more ambitious in scale. His wartime experiences led to a lifelong dedication to peace and a profoundly felt abhorrence for the inhumanity of war. Mastroianni made a large number of monumental sculptures on the theme of war throughout his career,of which the monument in Turin was the first; other examples include his more machine-like Monumento alla Resistenza Italiana (‘Monument to the Italian Resistance’),1964–69,and Monumento ai Partigiani del Canavese (‘Monument to the Partisans of Canova’),1969.

Mastroianni’s work successfully captured the mood of the moment in Italy and met with considerable acclaim. He might have been content to continue making work in the same figurative expressionist vein,but instead he made a sharp break and moved towards abstraction. Part of his inspiration seems to have been his rediscovery of another part of the Italian modernist tradition in the work of the leading futurist Umberto Boccioni. He became interested in Boccioni’s use of interpenetrating forms,and even more by the futurist preoccupation with movement and dynamism. Boccioni’s rarer sculptures,notably the celebrated Unique Forms of Continuity in Space,1913,seem to have been a direct source of inspiration for him. It is also clear that he looked at the paintings of Boccioni’s fellow futurist,Giacomo Balla. These may have encouraged him both to add colour to his own sculpture and to experiment with painting and graphic works,which form a considerable part of his postwar production – and of which some,perhaps surprisingly,were influenced by the Italian informalists such as Alberto Burri.

Another source of inspiration for Mastroianni came from across the Atlantic. He was one of the first European artists,and certainly one of the first sculptors,to be deeply affected by American abstract expressionism. Translating abstract expressionist brushwork into three-dimensional form,he made large and complex sculptures,like Battaglia (‘Battle’),1957,now in the Museo d’Arte Moderna in Rome,which convey some of the character of geological formations. As with some of Jackson Pollock’s drip-paintings,it is possible to feel that the abstract appearance of these works conceals a figurative programme – that Battaglia,for example,is so named because it can be read without difficulty as a group of warriors in combat. At the height of this phase Mastroianni was awarded the National Prize for sculpture at the 1958 Venice Biennale.

This did not,however,complete the trajectory of his development. In his late work he returned to the futurist sources which had attracted him in the period immediately following the Second World War,and began to examine them even more profoundly. One of the things which most interested the futurists was modern industry and technology,and they proclaimed that machine forms were superior to inherited classical ones. As the First Futurist Manifesto had declared: ‘A racing automobile is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace’. In the grip of this renewal of futurist influence Mastroianni took the organic forms he had appropriated from the abstract expressionists and transformed them into more definite shapes which resembled fragments of machines. He then organised these machine fragments into complex structures which still had the rhythmic energy of abstract expressionist calligraphy. In these final works he looked for a way to unite spontaneity and liberty of form with the ethos of a technological civilization.

Edward Lucie-Smith

Died February 23,Marino,Italy,1998

Chronology

-

Mastroianni in his studio

-

Hiroshima, 1960

-

Monumento alla Resistenza Italiana, 1964-69