The 11th

LaureateArchitecture

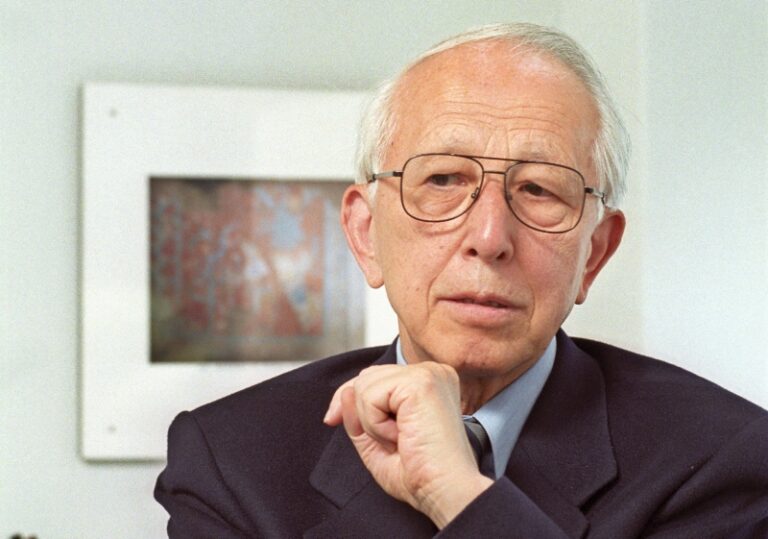

Fumihiko Maki

The arc of Fumihiko Maki’s career is vividly expressed in his Hillside Terrace project in Tokyo,begun in 1966 and continually updated and extended over a 30-year period. His early,cubic rationalism gradually developed into the preoccupation with lightness and dematerialization which informed major works such as the Fujisawa Gymnasium of 1984. Maki’s writings,as well as his buildings,evidence his profound awareness of the symbolic power of architecture; he wrote of Fujisawa’s simultaneously sharp and soft symbolizing the ambiguity of the modern world. His architecture is both rational and humane,historically aware yet unashamedly modern. In large-scale as well as domestic works,Maki’s lightness of spirit is expressed through a parallel lightness of form

Biography

Sometimes,there is a kind of perfection in the arc of a working life. For Fumihiko Maki that arc is not only distinct but solid. The history of this master of articulated modernism begins and ends - well,perhaps not quite yet - in a 500m stretch of Hachiyama-cho,which lies at the more affluent end of Tokyo’s Shibuya district. At the far end of Hachiyama-cho,where it hits the main junction,on the left,is the first element of the Hillside Terrace development – Maki’s breakthrough project. In 1969,forested land stood in the way of any further development of the fashionable Daikanyama district. The landowners presciently invited Maki to develop a strategic development masterplan for the site that would not depend on rapid paybacks.

Maki’s reputation was founded on an acute,intellectual grasp of architecture that had been honed at Tokyo (under Kenzo Tange) and Harvard universities; and,in particular,in a two-essay booklet that he published in 1964. It carried the title Investigations in Collective Form,and in it he said something of enduring prescience: ‘We have so long accustomed ourselves to conceiving of buildings as separate entities,that today we suffer from an inadequacy of spatial language to make meaningful environments.’ The words still ring true.

It was a mission statement whose physical starting point was the first phase of Hillside Terrace. Maki’s aim was to bring a rigorously detailed and carefully articulated approach to architecture; new buildings could be utterly modernist,but they had to relate to what was around them in organic,step-by-step developments rather than the sudden pyrotechnics of Big Bang design.

Maki likens the culture of architecture to the movement of waves: ‘The different waves collide and interfere with one another,some disappearing and others merging to form a bigger wave. Every day we experience and participate in the waves that began in the early years of the 20th century.’

The challenge at Hillside Terrace was to insert radical architecture that made sense,that fitted and fractalised itself acceptably. Gazing along the façades of the first three phases of the buildings - apartments above retail,circulation and small plazas - two things strike home. First,that Maki understood just how far modernist concrete and glass could be pushed before control over detail was lost; no showing off,in other words. From the start,he was confident enough in his approach not to seek embellishment.

The second issue is the brilliantly successful mixture of forms. No two phases in the early developments are the same. But stand anywhere - on the pavement,across the street - and gaze along the façades: they just flow. The projections,indents,scribed lines in the concrete,the tiling and the shadow angles are all part of tightly controlled,actual,and inferred,perspectives. And because of this,and from any angle,the massing of façades and voids appear to be interlocked. There is simply nothing to disagree with.

This is not surprising. Maki has never - even in his many internationally acclaimed projects since then - peddled confrontation or high-risk aesthetics. Instead,the risk is in his search for subtle harmonics of space and context,which have not always been associated with modernist architecture that may be riveting but can seem isolated from physical or cultural contexts. There are clues to Maki’s brand of holistic modernism in those he is prone to quote. The poet Octavio Paz,for example,who said that for every thousand people there are a thousand modernisms. He also cites Kafka’s dictum that anxiety forms the core of human existence - an anxiety that still lies at the heart of architecture.

There are clues,too,in Maki's recollections of his Tokyo childhood: the ‘liberating magic’ of seeing occasional white houses among the uniform browns,greys and greens of the city’s Yamanote district; and the deeply rooted idea that stimulated his boyhood years in the 1930s: Tokyo as a city seamed with alien areas,dark,secret places and endlessly overlapping scenes - a discovery of the present that was simultaneously physical and imagined,received and recreated.

Here,then,is a modernist who remains pathologically unable to separate architecture from context or from the responses of individuals; form following function is simply not good enough because,for him,the question of function triggers a cascade of contextual considerations.

Maki’s architecture arises from a landscape of small domains which people experience as uniquely singular realities. ‘The contemporary urbanite’,he argues,‘caught up in the seemingly spectacular,complex and enormous phenomenon of the city,is able to acquire only small,scattered domains.’ And there is even something almost carnal about this territorial sense: ‘Territory is entered and wraps itself around the individual.’

Which is more or less what happens to the stroller in Hillside Terrace - certainly in the earlier phases,where the connections of external space are very subtly achieved; and notably in the way Maki took pains to save and incorporate an ancient shrine and kofun burial mound into part of one of the courtyards. Time has shown such an approach to be sustainable: in a city where property values have made architecture an ephemeral,knock-down-drag-out affair,Hillside Terrace has endured virtually unmodified. This is architecture based not on the dysfunctional absurdities of being and time,but on optimism and the creation of small,spatial certainties which,in Hachiyama-cho,unfold step by carefully articulated step; this is a modernist evolution of the species in a series of increasingly transparent and finely etched buildings which,in its final,razor-shadowed flowering at Hillside Terrace West,becomes almost ethereal.

Jay Merrick

Chronology

The 4th Gold Medal,International Union of Architects (UIA).

-

Hillside Terrace Apartments

-

Tokyo Church of Christ

-

The Nippon Convention Centre

-

Kaze-no-Oka Crematorium

-

At his office