The 8th

LaureateSculpture

César

César played an important part in the Dada revival of the early 1960s,even though his attitudes to the founding father of Dada,Marcel Duchamp,were ambiguous: where Duchamp was a maker and an intellectual,Cesar thought he himself was ‘only a maker’. What he was making at that time were ‘Compressions’,cars that had been crushed into heavily compacted forms by wreckers’ presses. He went on to make vastly enlarged sculptures of body parts,particularly his own thumb. Later he showed classical influences in much the same way that Picasso had done – in fact,Picasso was the only artist César would admit to having been influenced by. César tried ceaselessly to reinvent: as he once remarked,‘In spite of myself,I’ve learned the difference between academicism and classicism – between copying something yet again,and beginning it over again.’

Biography

César’s attitudes to the founding father of French dadaism,Marcel Duchamp,were respectful but ambiguous. While Duchamp was both maker and intellectual,César said,he himself was only a maker.

In 1960,when he first became aware of the dada revival through the work of his friends and of Americans such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg,César began to create his ‘Compressions’,using the huge mechanical presses employed in crushing wrecked automobiles. Although these works might seem to have aligned him with the Duchampian cult of the readymade,for César it was the fascination of the process itself which was decisive. In the mid-1960s he similarly became fascinated with the mechanical pantograph,which can be used to create enlarged versions of quite small objects. Asked in 1965 to contribute to a thematic exhibition on the subject of The Hand at the Claude Bernard Gallery in Paris,he offered an enlarged version of his own thumb. Later he was to make enlargements of other body parts – a hand and a female breast. Because he wanted the enlarged Thumb to have a contemporary colour and texture,César started to experiment with polyurethane,and was inspired by the degree to which this substance expanded with the addition of the curing agent freon. This,in turn,led to the creation of his Expansions,where the polyurethane was allowed to take its own form. In keeping with the spirit of the time,César often turned the making of these Expansions into public ceremonies. In the 1970s,further experiments led to his plexiglass Compressions which,after the manner of Arman,incorporated extraneous objects,such as a pair of shoes.

César trained as an artist during the Second World War,first in Marseilles and then,in 1942,at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in occupied Paris. Within two years lack of money forced him back to Marseilles,where he made a living as a black-marketeer. He was only able to return to the profession of artist gradually,and the choice of low-cost materials for much of his sculpture is partially informed by this period in his life. His earliest work,now almost entirely lost,consisted of metal held together by plaster. In 1952,he started to make sculptures from bits of discarded scrap metal that he welded together to make both animal forms and human figures. This was not entirely an aesthetic choice,but was forced upon him by the fact that he had no money to buy blocks of stone or to pay for bronze-casting,whereas the material he used cost nothing. He was also well aware of the example set by Picasso and Julio González,both of whom had made welded-metal sculpture between the wars. César’s work soon attracted attention by its exuberance and wit,and in 1956 a one-man show at the Venice Biennale established his international reputation.

César was always restlessly experimental and he was not long in moving away from the kind of work that had established his reputation,even though he never abandoned welded sculpture altogether. His first departure was a series of flattened plaque-like sculptures made in the late 1950s,which were a product of his admiration for the Franco-Russian painter Nicolas de Staël. Soon afterwards,he became involved with the Nouveau Réaliste group founded by the critic Pierre Restany in 1960. Not only were most of the group younger than himself,but its best known participants – Yves Klein,Jean Tinguely,Christo and Arman – were very different artists from César. Where he began as a figurative expressionist (albeit one with a paradoxical attraction to Picasso’s variety of classicism),the other Nouveaux Réalistes were much closer to the tradition of dada.

César always remained true to his essentially classical roots and the most important of his later classical pieces is the beautiful Centaur made in 1982–83 as a homage to Picasso,whom César continued to regard as the only artist who had truly influenced him. As he once remarked,‘In spite of myself,I’ve learned the difference between academicism and classicism – between copying something yet again,and beginning it over again.’

Edward Lucie-Smith

He passed away on December 6,1998,Paris

Chronology

-

César in Gennevilliers, 1961

-

César in Gennevilliers, 1961

-

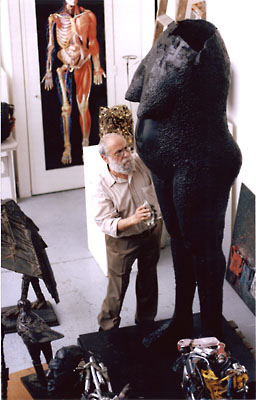

La Centaure, Paris, 1983

-

Thumb, La Defance, Paris, 1993.

-

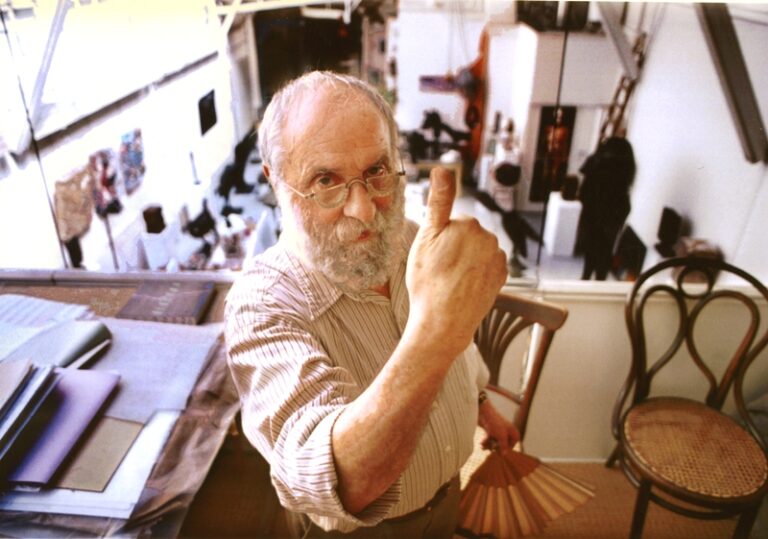

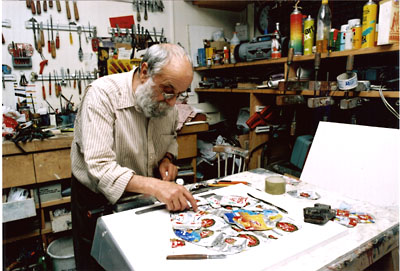

César in his studio, 1996.

-

César in his studio, 1996.