The 1st

LaureateMusic

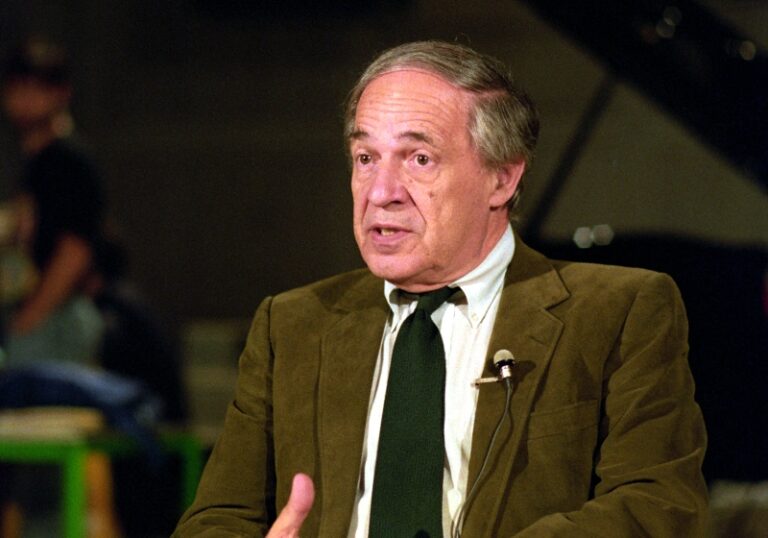

Pierre Boulez

Although to many music-lovers today Pierre Boulez is best known as a conductor,his influence as a composer also remains very strong. During the 1950s and 1960s,he was a pioneer of a highly deterministic approach to composition which at times attempted to control every aspect of a piece mathematically. Although this technique was fairly quickly abandoned even by Boulez himself,its influence can still be felt. He also established the leading research centre for music and science at IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique),of which he was director from 1977-91,and the performance group Ensemble Intercontemporain. His choice of conducting repertoire reflects a fascination with innovation in music,and his superb ear is both feared and admired by musicians.

Biography

The great debate among avant-garde composers in the 1950s centred on the question of control: how should the musical material in their compositions be organised? In 1951,the American composer John Cage was using chance methods – the I Ching and the toss of coins – to create the sequence of events in his Music of Changes for two pianos. Meanwhile in Europe,in 1952,Pierre Boulez completed the first book of a two-piano composition called Structures,continuing his unique evolution of a method of ‘total serialism’,a method in which the musical elements of pitch,duration,rhythm,timbre,articulation and dynamic were organised into series. Cage’s method attempted to ‘let sounds be themselves’. Boulez,on the other hand,set out to order and control sounds to a degree never heard before. The remarkable fact is that Music of Changes and Book Two of Structures both sound very similar – chaotic,almost random,and completely destructive of traditional tonality.

Boulez’s move towards ‘total’ or ‘integral’ serialism was partly influenced by the composition Mode de Valeurs et d’Intensités,1949,by Olivier Messiaen,in whose class at the Paris Conservatoire Boulez had studied composition. Messiaen also led summer schools in Darmstadt,at which Boulez and other avant-garde composers analysed and performed new works as well as music by Schoenberg,Debussy and Webern. Although serialism was a number-based technique,much of Boulez’s inspiration was poetic rather than mathematical. He was greatly influenced by James Joyce,René Char,e e cummings and Stéphane Mallarmé,whose Un coup de dés,in which text is fragmented across the page like flotsam from a shipwreck,contains the prophetic line ‘Un coup de dés n’abolira jamais le hasard’ (‘One throw of the dice will never abolish chance’). Boulez’s setting of Char’s Le Marteau sans Maître,1953–54,is perhaps his most beautiful composition – pointillistic,full of textural and rhythmic nuance and variety. It also introduced a grouping of instruments that has since provided a model for innumerable contemporary chamber ensembles: flute,guitar,viola,vibraphone,xylophone,percussion and voice. Le Marteau sans Maître uses serial technique but,as Boulez commented,‘it had to be infinitely more supple and lend itself to all kinds of invention… There is in fact a very clear element of control,but starting from this strict control and the work’s overall discipline there is also room for what I call local indiscipline – a freedom to choose,to decide and to reject.’

By this time,Boulez had become the unquestioned leader of the European modernist avant-garde. Other composers,such as Karlheinz Stockhausen,Luciano Berio and György Ligeti,had been drawn to Darmstadt in part by Boulez’s iconoclastic and anti-historical posture. When Cage arrived,these composers struggled to incorporate chance methods into their work. Boulez,on the other hand,attacked the ‘aleatoric’ in music and continued to pursue ideas of purity and abstraction.

These ideas increasingly led to the development and use of new technologies for their realisation. Between 1969 and 1975,Boulez established the leading European research centre for music and science at IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et de Co-ordination Acoustique/Musique) of which he was director from 1976–91,and in 1976 – the year that he was named Professor at the Collège de France – he announced the creation of the performance group Ensemble Intercontemporain. These two bodies have since dominated French and European contemporary musical culture,with a string of seminal compositional and performance events emanating from IRCAM’s base below ground near the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. These have included new works by almost every major avant-garde composer,as well as developments in computer-generated music and programming languages such as music4 and music5.

One important work to emerge from IRCAM was Boulez’s Répons,1981–86,for orchestra and digital equipment – a composition that Boulez has revised many times over the years. In the manner of James Joyce,he regards most of his compositions as works in progress. For Boulez as much as for Cage,every listening to a work should be a new and independent experience. Perhaps it is this awareness of the need for renewal,for fresh interpretation and realisation,that influenced the shift of emphasis in Boulez’s later career towards conducting,which demands a revision of the score in preparation for each new performance.

Boulez has conducted many of the major orchestras across the world,including the New York Philharmonic (of which he was musical director,1971–77),the BBC Symphony Orchestra (of which he was head conductor,1971–75),the Chicago Symphony,the Cleveland Orchestra and the Vienna Philharmonic,yet he has restricted himself almost exclusively to a small repertoire of works by Debussy,Ravel,Stravinsky,Bartók,Varèse,Berg,Schoenberg,Webern,Messiaen,Wagner,Mahler,Strauss,and a few of his contemporaries – Luciano Berio,György Ligeti,Harrison Birtwistle,Elliott Carter and Frank Zappa.

This choice of repertoire presents a vision of Western music in the twentieth century which is unfailingly Eurocentric (the Americans Carter and Zappa both wrote music in the manner of the European avant-garde) and focused upon musical innovation. In this,as in so many aspects of his artistic life,Boulez is unapologetic and defiant. He has never lost the urge to challenge the listener,the performer,and indeed himself.

Andrew Hugill

Chronology

Sonatine (flute and piano)

-

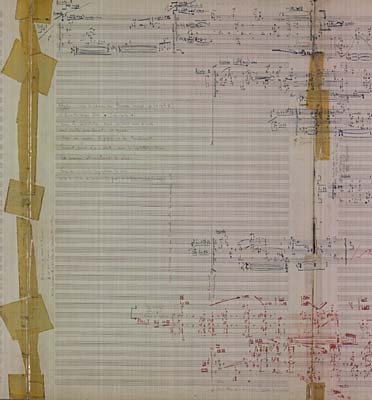

Troisieme Sonate pour piano

-

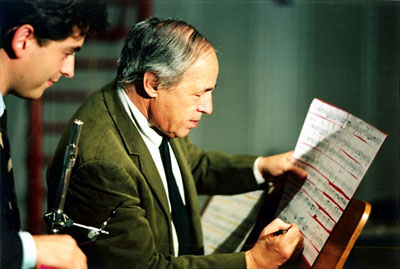

Pierre Boulez recording

-

©The Sankei Shimbun(1989)