The 5th

LaureateTheatre/ Film

Maurice Béjart

It was during his formative Parisian period in the 1950s,when he choreographed over 30 new ballets,that Maurice Bejart introduced kicking and screaming on to the ballet stage the ostensibly ‘unballetic’ themes of existential alienation,the quest for meaning in a godless universe and the psychic traumas endemic to both genius and madness. In 1960 he established the Ballets du XXieme Siècle at the Theatre de la Monnaie in Brussels,where he staged more than forty productions,the most famous,perhaps,being his controversial reinterpretation of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps. Bejart’s towering achievement has been to restore to ballet a true sense of ritual,and he has succeeded in attracting a new and younger public to a medium previously afflicted by cultural arthritis.

Biography

On the first page of his autobiographical memoir,Un instant dans la vie d’autrui (‘An Instant in Another’s Life’),and as though in order to pre-empt the kind of crass journalistic query with which every artist is plagued,Maurice Béjart wrote: ‘I am a choreographer because there’s nothing else I know how to do.’ And,further down on the same page,he added whimsically: ‘Artists (interpreters no less than creators) are akin to prostitutes. Akin? Why “akin”? The artist is a prostitute! If he experiences ecstasy,if he “comes”,so much the better,but it isn’t indispensable. It’s not his inalienable right. He isn’t there for that. His job is to make the public come.’

For Béjart,these two aphoristic declarations,which he undoubtedly means us to take quite literally,have served as both a credo and a manifesto. It may well be that he possesses several other talents but,apart from the publication of a novel (Mathilde ou le Temps perdu,a reflection of his lifelong obsession with Wagner),he has never done anything as an artist but dance and create ballets for others to dance. Such is his almost monomaniacally single-minded preoccupation with the dramatic and expressive powers of his chosen medium,he has actually split the chronology of his own life in two: ‘little Maurice Berger’ (his real name) ‘born in 1927,died some time during the War,’ he declared; and ‘the choreographer Béjart was born in 1955’ (the year in which Symphonie pour un homme seul,the ballet that made his reputation,was premièred). As for the bizarre comparison between aesthetic creation and prostitution,it is borne out by the paroxysmatic eroticism of much of his work and by his contemptuous rejection of ballet as a congenitally minor form,twee and tinselly,ephemeral and effeminate,of interest only to tired businessmen,queenish dilettantes and prim little middle-class girls.

It was during his formative Parisian period,when he choreographed over 30 new ballets,that Béjart created the flamboyantly anxiety-ridden Symphonie pour un homme seul,celebrated for its electronic score by Pierre Henry,the composer of musique concrète who would remain one of his most loyal collaborators. With that pioneering work,as also such others as Messe pour le temps présent,Bakhti and Nijinski,Clown de Dieu,in which he introduced,kicking and screaming,on to the ballet stage the ostensibly ‘unballetic’ themes of existential alienation,the quest for meaning in a godless universe and the psychic traumas endemic to both genius and madness,he became the apologue and ideologist of an idiosyncratic form of theatrical mysticism,one deeply influenced by certain age-old Oriental belief-systems and impregnated by the neo-expressionist violence of Pierre Henry’s electronic scores.

Writing of his choreographic biography Nijinski,Béjart once recalled that,in the hope of getting right under his protagonist’s skin,he endeavoured to speak to everyone who had ever encountered the great dancer,taught himself Russian and even started smoking Nijinski’s brand of cigarettes. For him,the Wagnerian ideal of ‘total theatre’ is no mere cant phrase but a complete investment of self.

In 1960 he established the Ballets du XXième Siècle and made both its and his base the splendid Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels. There he became something of a national institution,and every cultivated visitor to the Belgian capital would be expected to see the latest Béjart productions,of which there were to be more than forty. The most famous,perhaps,was his unique version of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps,a controversial reinterpretation of the most prestigious of all modern ballets. In Béjart’s staging – which subsequently toured the world – the first section was danced exclusively by men,the second by women,and the third,finally,by both sexes. By thus shaking off the cobwebby fripperies that had begun to encrust even what had once been regarded as a ballet of unparalleled savagery,he succeeded in attracting a whole new and younger public to a medium afflicted by cultural arthritis.

It might,in conclusion,be worth quoting Béjart again. ‘We have need of rites,’ he wrote in his autobiography. ‘Impossible to do without them. The proof is that everyone observes some rite or other,even if it should be a pale,debased image comparable rather to a tic,just as with those people who,when preparing their breakfast,make the selfsame gesture every morning without risking the slightest variation.’

Béjart’s towering achievement has been to restore to ballet,a form of spectacle in which what had been a solemn rite had indeed begun to degenerate into little more than a collection of nervous tics,a true sense of ritual.

Gilbert Adair

He passed away on 27 April,2007,Moscow

Chronology

Opens the ballet school l'association Mudra,renamed la Rudra Bejart in 1992

Author of 'Maurice Bejart' (in collaboration)

-

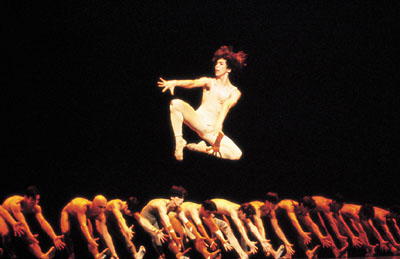

The Rite of Spring

-

The Rite of Spring

-

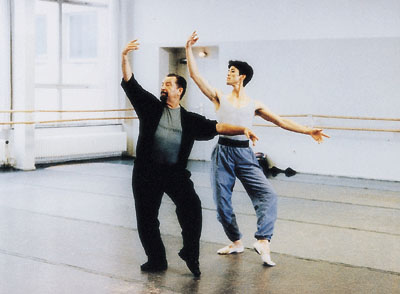

Rehearsing Bolero with N Takagishi

-

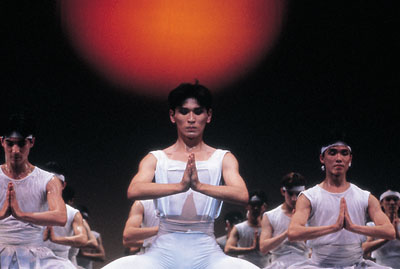

The Kabuki

-

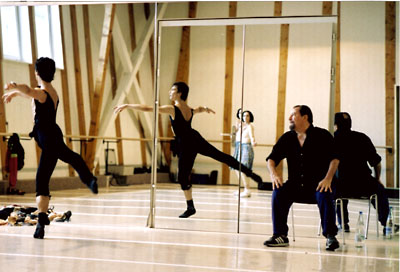

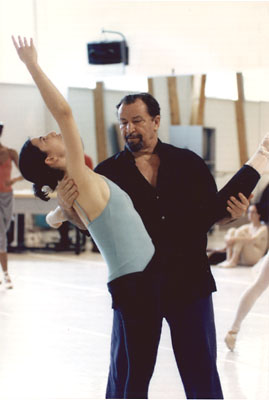

Bejart choreographing at Rudra Bejart Lausanne

-

Bejart choreographing at Rudra Bejart Lausanne