The 3rd

LaureatePainting

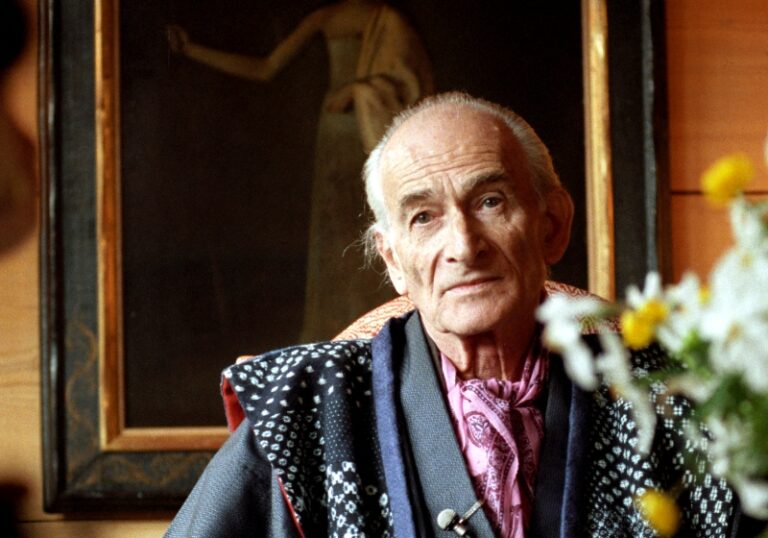

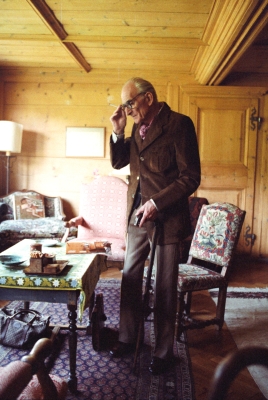

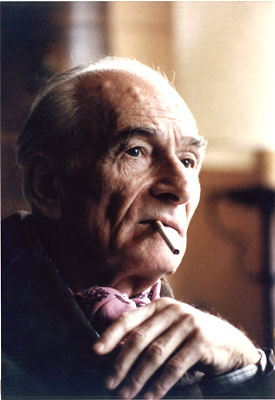

Balthus

Balthus was one of the twentieth century’s great figurative painters. His compositional and painterly techniques were undoubtedly brilliant,but his work is particularly unique in its psychological power – every picture seems to be a moment in some unexplained but deeply moving drama. His vision of the erotic language of dreams was suggestive of twentieth-century developments in psychoanalysis,while at the same time bringing him close to surrealism. He remained intentionally isolated from other artists,working in seclusion at his chateau in the Swiss Alps and deliberately rejecting the trappings of fame. His work has endured because of its originality,its intensity and above all its sense of the mystery of desire.

Biography

Count Balthasar Klossowski de Rola – professionally known as Balthus – combined in his art centuries of European mastery and a deep attachment to the refinements of Oriental culture. The poet Rilke noted this fascination with the Orient in commenting on Balthus’ suite of forty drawings,published in 1922,notwithstanding their resemblance to the graphic narratives of Frans Masereel. What seemed contradictory interests and alliances continued to inform Balthus’ conception of art,resulting both in his curiously isolated position among twentieth-century painters and the high regard in which he was held,by artists and the wider public,as a champion of the great tradition of monumental figure painting.

His parents were Polish,his father an art historian who became a painter,his mother a painter too and he grew up in Paris and Switzerland. What art schooling he needed he got at home and in Tuscany,the Louvre and major museums everywhere. He continued to learn about materials and form from the great painters of the past,notably Piero della Francesca and Poussin,and of more recent times,including Ingres,Seurat,Bonnard,Derain and Courbet. Courbet and Balthus would seem to represent contrary attitudes to art. Courbet,asserting the primacy of realism in his subjects,would be astonished at the balletic unreality of Balthus’ scenes and the hieratic refinement of his figures,which are indebted to two other major sources,Georges de la Tour (the seventeenth-century painter of religious and genre scenes) and Georges Seurat (the nineteenth-century painter who invented systems of expressive composition and exact colouration to bridge the gap between classical formalities and modern informal naturalism as developed so outrageously by the impressionists).

Balthus began to exhibit in the thirties,too late to be recognized as a painter dedicated to the classsicism to which the famous ‘call to order’ had summoned French and Italian artists,causing many of them to moderate their modernism and reaffirm their classical roots. Yet,for all the classicism of his compositions and the elegance of his figures,order itself was clearly not his aim. Even his major portraits,of Derain with a model and of Miró with his daughter,are moments in an unexplained drama. This was even more striking when he painted girls in early adolescence,naked or dressed but often sprawled in abandonment,for the attention sometimes of another being in the picture as well as for the viewer of the painting. Sensuality was admitted by Balthus as by Courbet,yet Balthus’ invitation is not to possess tangible flesh but to see and admire desirable forms,marking his work as a contribution to a long history of such forms in western art,from the elegance of late Gothic and Botticelli to the mannerism of Parmigianino and the romanticism of Fuseli. No wonder Bonnard was interested in Balthus and Balthus in Bonnard: desire but do not touch.

In 1961 André Malraux wisely appointed Balthus to be head of the French Academy in Rome,his home until he moved into a chateau in the Swiss Alps in 1977. In 1963,again at Malraux’s request,he went to Japan to select an exhibition of Japanese art for Paris. There he met a Japanese painter who became his second wife; Japanese faces and forms are unmistakable in some of his paintings of the sixties and seventies. Otherwise Balthus’ later work frequently shows him revisiting earlier motifs and scenes,reworking them in more intensely formalized terms and with dry paint surfaces that suggest old walls. He has also developed an aspect of his pictorial stage craft,that associates him with surrealism. All Balthus’ scenes seem pregnant with undisclosed meaning. This is what made him so brilliant an illustrator of Emily Brontë’s fiercely romantic novel Wuthering Heights. His 1933 drawings even suggest the influence of the Pre-Raphaelite group that had formed in 1848,a year after the book’s original publication. In some of his paintings,from Le Chat de la Mediterranée,1949,showing a girl in a boat and a man-cat seated at a table,to his Grande composition au corbeau,1983–86,with its monumental nude girl,cat and raven attended by a miniature man,Balthus allows his imagination to reveal its irrational impulses and roam beyond the stiffly respectable drawing-rooms and boudoirs his figures generally inhabit.

There was a retrospective Balthus show at the Tate Gallery in London in 1968,when Balthus wanted his personal history excluded from the catalogue. Subsequent retrospectives in Europe and America have revealed him more completely. There have also been exhibitions of his subtle pencil drawings. His preparatory drawings for paintings he destroys. His other drawings make patent his skill and his humanity. His death in 2000 has left us with a powerful sense of an artist who liked to veil himself,his working processes,and often the finished picture in a cloak of mystery.

Norbert Lynton

Died February 18,Rossiniere,Switzerland,2001

Chronology

-

Balthus and family at home

-

Balthus and family at home

-

At his home

-

At his home

-

At his home